Identical twins originate from one egg cell that splits and gives rise to two embryos, but during development, one twin sometimes “vanishes”, leaving only one baby to be born.

Now, a new study hints that your DNA may reveal whether you started out as an identical twin in the womb, even if your twin disappeared long before your birth.

In the new study, published Tuesday (Sept. 28) in the journal Nature Communications, the researchers zoomed in on so-called epigenetic modifications found in twin DNA.

The term “epigenetic” refers to factors that can switch genes “on” or “off” without changing their underlying DNA sequence. For example, small molecules called methyl groups can cling like sticky notes to specific genes and prevent the cell from reading those genes, thus effectively switching them off.

According to the new study, the DNA of identical twins comes adorned with a characteristic pattern of sticky methyl groups. This pattern spans 834 genes and can be used to differentiate identical twins from both fraternal twins and non-twins, the authors found. And, in fact, based on these results, the team developed a computer algorithm that can reliably identify an identical twin based solely on the location of methyl groups across their DNA.

In theory, such a tool would also be able to spot someone who’d had a vanishing twin, although the new study didn’t test this idea.

Related: Seeing double: 8 fascinating facts about twins

In essence, this methyl group pattern is a kind of “molecular scar” left over from identical twins’ early embryonic development, said Robert Waterland, a professor of pediatrics and genetics at Baylor College of Medicine who was not involved in the new study.

“The authors have discovered an epigenetic signature of monozygotic twinning,” meaning twinning that stems from a single fertilized egg, or zygote, he said.

The genes coated in these methyl groups play various roles in cell development, growth and adhesion, meaning they help cells stick to one another. That said, based on the current study, it’s unclear how these methylated genes, in particular, might influence the growth, development or health of identical twins, Waterland said.

In investigating these scars of early development, the authors wanted to better understand why identical twinning occurs in the first place. Scientists know that the zygote splits at a certain point of development, but it has been a mystery as to why the splitting sometimes occurs.

“[The study] was driven by the fact that we knew very little about why monozygotic twins arise,” said first author Jenny van Dongen, an assistant professor in the Department of Biological Psychology at Vrije University (VU) Amsterdam.

An estimated 12 percent of human pregnancies start out as multiple pregnancies, but less than 2 percent are carried to term, meaning the rest result in a so-called vanishing twin, according to a 1990 report in the International Journal of Fertility and Sterility.

Overall, in cases where both twins make it to term, fraternal twins are generally more common than identical ones.

Evidence suggests that genetics influences a mother’s likelihood of bearing fraternal twins, which happens when two eggs get fertilized at the same time. For instance, studies show that fraternal twinning can run in families and that genes involved in hyperovulation seem to be at play, van Dongen said.

By comparison, the prevalence of identical twins is fairly consistent across the world, occurring in roughly 3 to 4 out of every 1,000 births, which hints that genetics doesn’t drive the phenomenon. The question is, what does?

“It’s really a mystery in developmental biology,” said senior author Dorret Boomsma, a professor in the Department of Biological Psychology at VU Amsterdam.

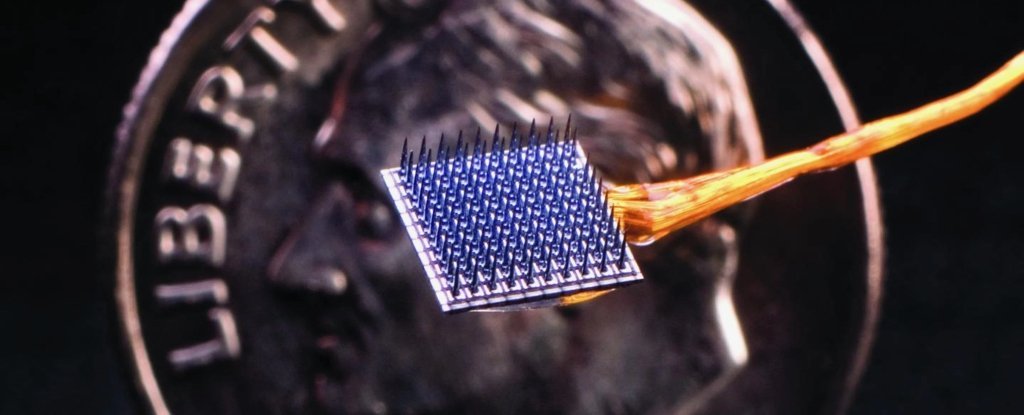

The team wondered if the solution to this mystery might be encoded in the methyl groups decorating a person’s DNA, since the molecules help to control embryonic development in its very earliest stages. And thanks to special proteins called methyltransferases, the methyl groups added to our DNA in development get copied down as our cells continue to divide, meaning they can stick around into adulthood.

For the new study, the team pulled epigenetic data from six large cohorts of twins, for a total of more than 6,000 individuals. The cohorts included both identical twins and fraternal twins as well as some non-twin family members of these individuals. By including the fraternal twins, the team could check whether any epigenetic patterns seen in identical twins were actually unique to them and not common to all kinds of twins.

Related: Having a baby: Stages of pregnancy by trimester

Most of the DNA methylation data came from blood samples collected from adults, but one data set consisted of cheek swab samples from children. And across all of the samples, the team found the same distinct patterns of methylation in identical twin DNA.

“The fact that they see the same things in those cells is reassuring,” because that shows that the pattern isn’t specific to one type of cell, Waterland said.

This implies that the telltale methylation took place super early in development, before specialized tissues, like the heart or lungs, began to form. When methyl groups stick to DNA at this stage, methyltransferases pass down the molecules to all subsequent daughter cells, regardless of what cell type they eventually become.

Because some of the data sets included DNA samples collected at multiple points in time, the team could double-check how stable these methylation patterns were over several years. “They found that these methylation states are very stable in an individual,” which further strengthens the idea that these methyl groups could conceivably stick around from fertilization to adulthood, Waterland said.

“It seems that something happens very early on in development, and that this remains written in the methylation pattern of different cell types in our body,” van Dongen said. “It remains archived in our cells.”

That said, for now, it’s unclear what exact effect these methyl groups have on gene expression (the turning “on” or “off” of a gene), or whether the methylation pattern represents a cause, effect or byproduct of identical twinning, she noted.

“To really understand the exact steps that take place early on in embryonic development that lead to the formation of monozygotic twins, we really need functional studies,” van Dongen said, referring to research looking at how these changes affect actual cells.

The team plans to conduct such studies using animal models and human cells in lab dishes; they may also use models of the human embryo known as blastoids.

In the future, the team could also survey a larger swatch of epigenetic modifications to the genome, to see if the methylation pattern extends beyond the 800-odd genes already identified, Waterland said.

The new study covered hundreds of thousands of potential methyl group sticking points, but there are plenty more to be probed, he said.

Related Content:

7 diseases you can learn about from a genetic test

Genetics by the numbers: 10 tantalizing tales

10 amazing things scientists just did with CRISPR

This article was originally published by Live Science. Read the original article here.

Local7 years ago

Local7 years ago

Crime8 years ago

Crime8 years ago

Local8 years ago

Local8 years ago

Top Stories2 years ago

Top Stories2 years ago

Crime8 years ago

Crime8 years ago

Crime8 years ago

Crime8 years ago

Sports10 months ago

Sports10 months ago

Crime8 years ago

Crime8 years ago

You must be logged in to post a comment Login