Imagine a Universe where you could point a spaceship in one direction and eventually return to where you started. If our Universe were a finite donut, then such movements would be possible and physicists could potentially measure its size.

“We could say: Now we know the size of the Universe,” astrophysicist Thomas Buchert, of the University of Lyon, Astrophysical Research Center in France, told Live Science in an email.

Related: 10 wild theories about the Universe

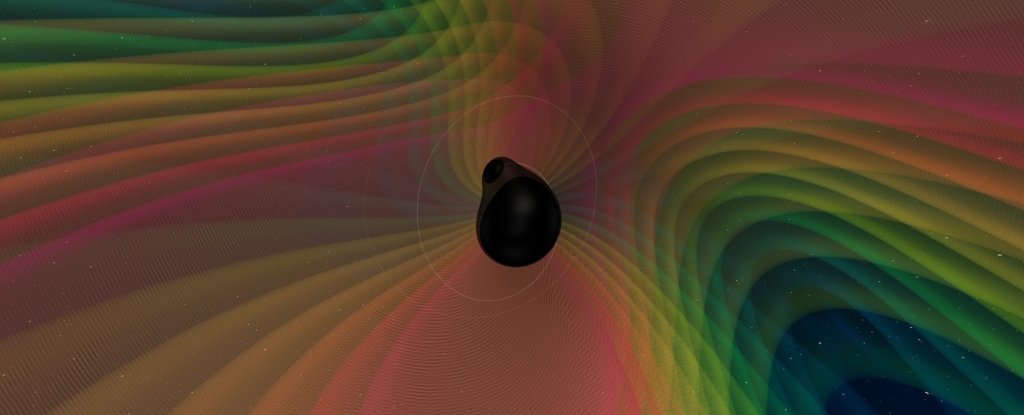

Examining light from the very early Universe, Buchert and a team of astrophysicists have deduced that our cosmos may be multiply connected, meaning that space is closed in on itself in all three dimensions like a three-dimensional donut.

Such a Universe would be finite, and according to their results, our entire cosmos might only be about three to four times larger than the limits of the observable Universe, about 45 billion light-years away.

Physicists use the language of Einstein’s general relativity to explain the Universe. That language connects the contents of spacetime to the bending and warping of spacetime, which then tells those contents how to interact. This is how we experience the force of gravity.

In a cosmological context, that language connects the contents of the entire Universe — dark matter, dark energy, regular matter, radiation and all the rest – to its overall geometric shape.

For decades, astronomers had debated the nature of that shape: whether our Universe is ‘flat’ (meaning that imaginary parallel lines would stay parallel forever), ‘closed’ (parallel lines would eventually intersect) or ‘open’ (those lines would diverge).

Related: 8 ways you can see Einstein’s theory of relativity in real life

That geometry of the Universe dictates its fate. Flat and open Universes would continue to expand forever, while a closed Universe would eventually collapse in on itself.

Multiple observations, especially from the cosmic microwave background (the flash of light released when our Universe was only 380,000 years old), have firmly established that we live in a flat Universe. Parallel lines stay parallel and our Universe will just keep on expanding.

But there’s more to shape than geometry. There’s also topology, which is how shapes can change while maintaining the same geometric rules.

For example, take a flat piece of paper. It’s obviously flat – parallel lines stay parallel. Now, take two edges of that paper and roll it up into a cylinder. Those parallel lines are still parallel: Cylinders are geometrically flat. Now, take the opposite ends of the cylindrical paper and connect those. That makes the shape of a donut, which is also geometrically flat.

While our measurements of the contents and shape of the Universe tell us its geometry – it’s flat – they don’t tell us about the topology. They don’t tell us if our Universe is multiply-connected, which means that one or more of the dimensions of our cosmos connect back with each other.

Look to the light

While a perfectly flat Universe would extend out to infinity, a flat Universe with a multiply-connected topology would have finite size. If we could somehow determine whether one or more dimensions are wrapped in on themselves, then we would know that the Universe is finite in that dimension. We could then use those observations to measure the total volume of the Universe.

But how would a multiply-connected Universe reveal itself?

A team of astrophysicists from Ulm University in Germany and the University of Lyon in France looked to the cosmic microwave background (CMB). When the CMB was released, our Universe was a million times smaller than it is today, and so if our Universe is indeed multiply connected, then it was much more likely to wrap in on itself within the observable limits of the cosmos back then.

Today, due to the expansion of the Universe, it’s much more likely that the wrapping occurs at a scale beyond the observable limits, and so the wrapping would be much harder to detect. Observations of the CMB give us our best chance to see the imprints of a multiply connected Universe.

Related: 5 reasons we may live in a multiverse

The team specifically looked at the perturbations – the fancy physics term for bumps and wiggles – in the temperature of the CMB. If one or more dimensions in our Universe were to connect back with themselves, the perturbations couldn’t be larger than the distance around those loops. They simply wouldn’t fit.

As Buchert explained to Live Science in an email, “In an infinite space, the perturbations in the temperature of the CMB radiation exist on all scales. If, however, space is finite, then there are those wavelengths missing that are larger than the size of the space.”

In other words: There would be a maximum size to the perturbations, which could reveal the topology of the Universe.

Making the connection

Maps of the CMB made with satellites like NASA’s WMAP and and the ESA’s Planck have already seen an intriguing amount of missing perturbations at large scales. Buchert and his collaborators examined whether those missing perturbations could be due to a multiply-connected Universe.

To do that, the team performed many computer simulations of what the CMB would look like if the Universe were a three-torus, which is the mathematical name for a giant three-dimensional donut, where our cosmos is connected to itself in all three dimensions.

“We therefore have to do simulations in a given topology and compare with what is observed,” explained Buchert. “The properties of the observed fluctuations of the CMB then show a ‘missing power’ on scales beyond the size of the Universe.”

A missing power means that the fluctuations in the CMB are not present at those scales. That would imply that our Universe is multiply-connected, and finite, at that size scale.

“We find a much better match to the observed fluctuations, compared with the standard cosmological model which is thought to be infinite,” he added.

“We can vary the size of the space and repeat this analysis. The outcome is an optimal size of the Universe that best matches the CMB observations. The answer of our paper is clearly that the finite Universe matches the observations better than the infinite model. We could say: Now we know the size of the Universe.”

The team found that a multiply-connected Universe about three to four times larger than our observable bubble best matched the CMB data. While this result technically means that you could travel in one direction and end up back where you started, you wouldn’t be able to actually accomplish that in reality.

We live in an expanding Universe, and at large scales the Universe is expanding at a rate that is faster than the speed of light, so you could never catch up and complete the loop.

Buchert emphasized that the results are still preliminary. Instrument effects could also explain the missing fluctuations on large scales.

Still, it’s fun to imagine living on the surface of a giant donut.

Related content:

11 fascinating facts about our Milky Way galaxy

5 reasons we may live in a multiverse

The 18 biggest unsolved mysteries in physics

This article was originally published by Live Science. Read the original article here.

Local7 years ago

Local7 years ago

Crime8 years ago

Crime8 years ago

Local8 years ago

Local8 years ago

Top Stories2 years ago

Top Stories2 years ago

Crime8 years ago

Crime8 years ago

Crime8 years ago

Crime8 years ago

Sports10 months ago

Sports10 months ago

Crime8 years ago

Crime8 years ago

You must be logged in to post a comment Login