Microbes fished from the stomachs of cows can gobble up certain kinds of plastic, including the polyethylene terephthalate (PET) used in soda bottles, food packaging, and synthetic fabrics.

Scientists uncovered these microbes in liquid that was drawn from the rumen, the largest compartment of a ruminant’s stomach; ruminants include hooved animals like cattle and sheep, which rely on microorganisms to help break down their diet of coarse vegetation.

The rumen acts as an incubator for these microbes, which either digest or ferment foods consumed by a cow or other ruminant, according to the University of Minnesota.

The researchers suspected that some microbes lurking in a cow’s rumen should be capable of digesting polyesters, substances whose component molecules are linked by so-called ester groups.

That’s because, due to their herbivorous diets, cows consume a natural polyester produced by plants called cutin. As a synthetic polyester, PET shares a similar chemical structure to this natural substance.

Cutin makes up most of the cuticle, or the waxy outer layer of plant cell walls, and it can be found in abundance in the peels of tomatoes and apples, for example, said corresponding author Doris Ribitsch, a senior scientist at the University of Natural Resources and Life Sciences in Vienna.

Related: How much plastic actually gets recycled?

“When fungi or bacteria want to penetrate such fruits, they are producing enzymes that are able to cleave this cutin,” or split the chemical bonds within the substance, Ribitsch told Live Science.

Specifically, a class of enzymes called cutinases can hydrolyze cutin, meaning they jump-start a chemical reaction in which water molecules break the substance into bits.

Ribitsch and her colleagues have isolated such enzymes from microbes in the past and realized that cows might be a source of similar polyester-munching bugs.

“These animals are consuming and degrading a lot of plant material, so it’s highly probable that you can find such microbes” living in the stomachs of cows, she said.

And, in fact, in their new study, published Friday (July 2) in the journal Frontiers in Bioengineering and Biotechnology, the researchers found that microbes from the cow rumen could degrade not only PET but also two other plastics – polybutylene adipate terephthalate (PBAT), used in compostable plastic bags, and polyethylene furanoate (PEF), made from renewable, plant-derived materials.

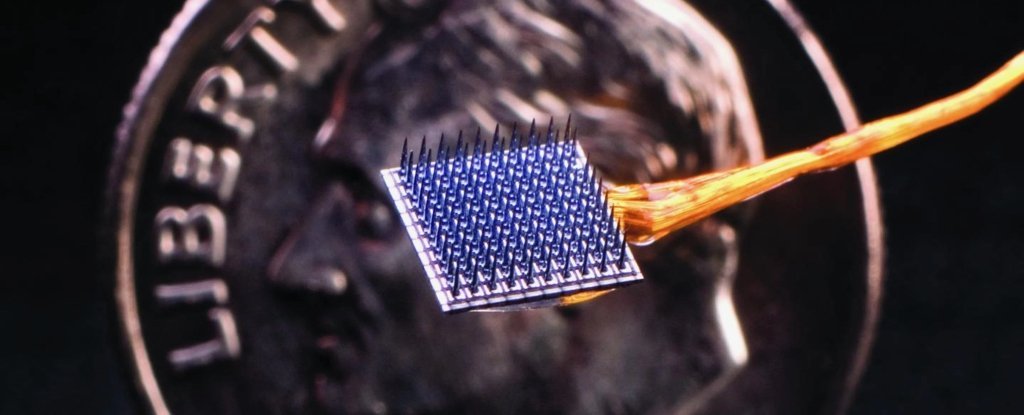

To assess how well these rumen-borne microbes could eat plastic, the team incubated each type of plastic in rumen liquid for one to three days. They could then measure the byproducts released by the plastics, to determine whether and how extensively the bugs broke down the materials into their component parts.

The rumen liquid broke down the PEF most efficiently, but it degraded all three kinds of plastic, the team reported.

The team then sampled DNA from the rumen liquid, to get an idea of which specific microbes might be responsible for the plastic degradation. About 98 percent of the DNA belonged to the bacteria kingdom, with the most predominant genus being Pseudomonas, of which several species have been shown to break down plastics in the past, according to reports in the journal Applied Microbiology and Biotechnology and the Journal of Hazardous Materials.

Bacteria of the genus Acinetobacter also cropped up in high quantities in the liquid, and likewise, several species within the genus have been shown to break down synthetic polyesters, according to a 2017 report in the Journal of Agricultural and Food Chemistry.

Looking forward, Ribitsch and her team want to fully characterize the plastic-eating bacteria in rumen liquid and determine which specific enzymes the bacteria use to break down the plastics.

If they identify enzymes that could potentially be useful for recycling, they can then genetically engineer microbes that produce those enzymes in large quantities, without the need to collect said microbes directly from cow stomachs.

In this way, enzymes can be produced easily and inexpensively, for use at industrial scales, Ribitsch said.

In that vein, Ribitsch and her team have already patented a recycling method in which textile materials get exposed to various enzymes in sequence; the team identified these enzymes in previous work.

The first batch of enzymes eats away at cloth fibers in the material, while the next batch of enzymes goes after specific polyesters. This works because each enzyme targets very specific chemical structures and therefore won’t break down just any material it encounters.

In this way, textiles that contain multiple materials can be recycled without first being separated into their component parts, Ribitsch explained.

Per the new study, cow rumens may represent another environment in which to discover these sorts of helpful enzymes, but such enzymes crop up in many places in nature, said David Levin, a molecular biologist and biotechnologist in the University of Manitoba Department of Biosystems Engineering who was not involved in the research.

For instance, the first bacterium found to be capable of consuming PET was Ideonella sakaiensis, a species involved in sake fermentation, Levin said. Certain marine organisms secrete cutinases that can break down plastic, as do various fungi that infect land plants, he noted.

Thus far, scientists have had luck finding plastic-eating enzymes that break down PET and biodegradable plastics like PBAT and PEF, but now, the real challenge lies in finding enzymes to break down more troublesome plastic products, Levin said.

For example, plastics like polyethylene and polypropylene are largely made up of strong bonds between carbon atoms, and this structure limits the ability of enzymes to grab hold of the molecules and jump-start hydrolysis, Ribitsch said.

So while scientists have already discovered, characterized, and commercialized enzymes to degrade PET, researchers are still on the hunt for microbes that can handle polyethylene and polypropylene, Levin said.

Levin and his lab have identified a few promising candidates on this front, but they are still figuring out how to maximize the bugs’ plastic-eating powers.

Ribitsch said her team also has an eye out for microbes that can consume polyethylene and wonders if the bugs might be lurking in the stomachs of cows.

“Maybe we can find, in such huge communities, like in the rumen liquid, enzymes that can also degrade polypropylene and polyethylene,” she said.

Related content:

How do we turn oil into plastic?

Plastic bag waste litters landscape (Infographic)

5 ways gut bacteria affect your health

This article was originally published by Live Science. Read the original article here.

Local7 years ago

Local7 years ago

Crime8 years ago

Crime8 years ago

Local8 years ago

Local8 years ago

Top Stories2 years ago

Top Stories2 years ago

Crime8 years ago

Crime8 years ago

Crime8 years ago

Crime8 years ago

Sports10 months ago

Sports10 months ago

Crime8 years ago

Crime8 years ago

You must be logged in to post a comment Login